Sea freight

Previous | Table of contents | Next

2.2.1 International shipping and trade

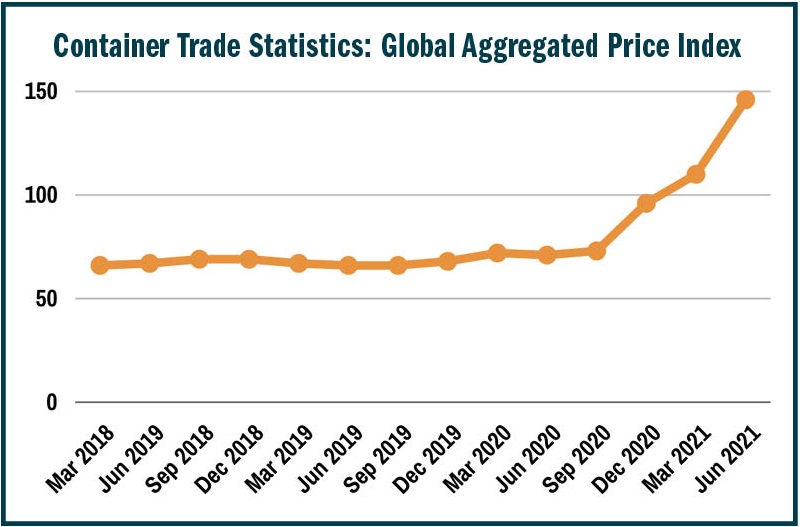

COVID-19 has driven a surge in demand for goods internationally. Government stimulus packages and low interest rates worldwide have boosted consumer and infrastructure spending, while lockdowns, border restrictions and limited travel opportunities have seen more consumers turning to shopping online, leading to an increase in containerised imports.

The long-lead time involved in increasing supply – that is, building more vessels and shipping containers – means that it will be some time before new stock is available to meet the global surge in demand for shipping services and alleviate increases in shipping rates.

Transport companies are prioritising those trade routes where demand (and hence transport prices) are highest. Some ports are being restricted or even removed from vessel calls due to congestion issues as vessels seek to minimise delays along priority routes, with high demand for shipping services causing shipping costs to rise globally.

Price impacts have been significant in Australia and internationally, with the largest impacts seen in long distance routes, such as Shanghai to Rotterdam. Increased demand in a supply-constrained environment is not the only issue affecting international shipping and trade.

"It is not uncommon to hear of Australian companies absorbing higher costs... to maintain market share (for import and export) and one has to wonder at what point will the cost of supply chain eventually be passed on to the consumer..."

—Brett Charlton, Freight Industry Reference Panel Member, speaking at the Regional Development Australia Forum in June 2021

When the MV Ever Given ran aground in the Suez Canal in March 2021, blocking one of the world’s busiest freight waterways, maritime became front page news in Australia. Although the vessel was freed within a week, the knock on impacts caused by the disruption were felt internationally for much longer, as ships were delayed and ports struggled to get through the backlog.

Fortunately, any impacts to Australia’s supply chain were relatively minor. Closer to home there was a larger maritime backlog caused with the detection of the virulent Delta variant of COVID-19 at terminals at the Yantian and Ningbo ports in China. Restrictions introduced to combat the spread of the virus led to increased container congestion and delays to shipping schedules.

From a port-handling perspective, these terminal closures impacted the movement of global shipping containers more than the Ever Given grounding in the Suez Canal. The vulnerable nature of global shipping is increasing pressure on the traditional ‘just in time’ approach to freight and supply chains.

Businesses are increasingly considering ‘just in case’ models which, while more reliable, incur greater cost due to the associated need for more storage.

| A closer look: Just in time versus Just in case |

|---|

|

Just in time and just in case are different approaches to freight distribution. As the name implies, just in time models deliver freight when and where it is needed. When supply chains are running efficiently with minimal disruption, this approach helps to keep costs down by minimising the need for excess storage. Just in case models, on the other hand, seek to maintain a stockpile of goods for future use, limiting the business’ reliance on efficient supply chains. Just in time processes are more vulnerable to supply chain shocks as they do not leave much room for error, such as if a supplier misses a shipment, transport is disrupted, or if the firm experiences a surge in demand. Just in time versus just in case represents the trade-offs between efficiency and resilience. |

2.2.2 Coastal shipping

Australia has a coastal trading regime that provides priority and unfettered operation to Australian vessels, and enables foreign-flagged vessels to carry domestic cargo under a temporary licence. Coastal shipping is important for a range of on-shore industries including mining, agriculture and refineries, moving a variety of freight including bulk commodities, petroleum and roll-on roll-off cargo. For much of this freight, coastal trading is the most efficient and sometimes the only way to move the volumes required without affecting the viability of Australian businesses and increasing costs for consumers.

While data for Australian vessels operating under a General License is not yet available for 2020-21, data reported by Temporary License holders indicates that in 2020-21, foreign-flagged vessels moved approximately 25.8 million tonnes of domestic cargo between Australian ports5. Coastal shipping is approximately 15 per cent of Australia’s domestic freight task.

From February to June 2020, as global responses to COVID-19 such as travel restrictions and the reduction of aviation services were being introduced, temporary license voyages fell by 7 per cent and volumes carried by around 11 per cent compared with the same period in 2019. However, coastal trading data indicates that overall cargo volumes have since recovered and remain relatively stable, indicating that domestic shipping has remained an effective way of moving goods around the country during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consultation on coastal trading reform is continuing with key stakeholders to identify and refine reform options.